Introduction

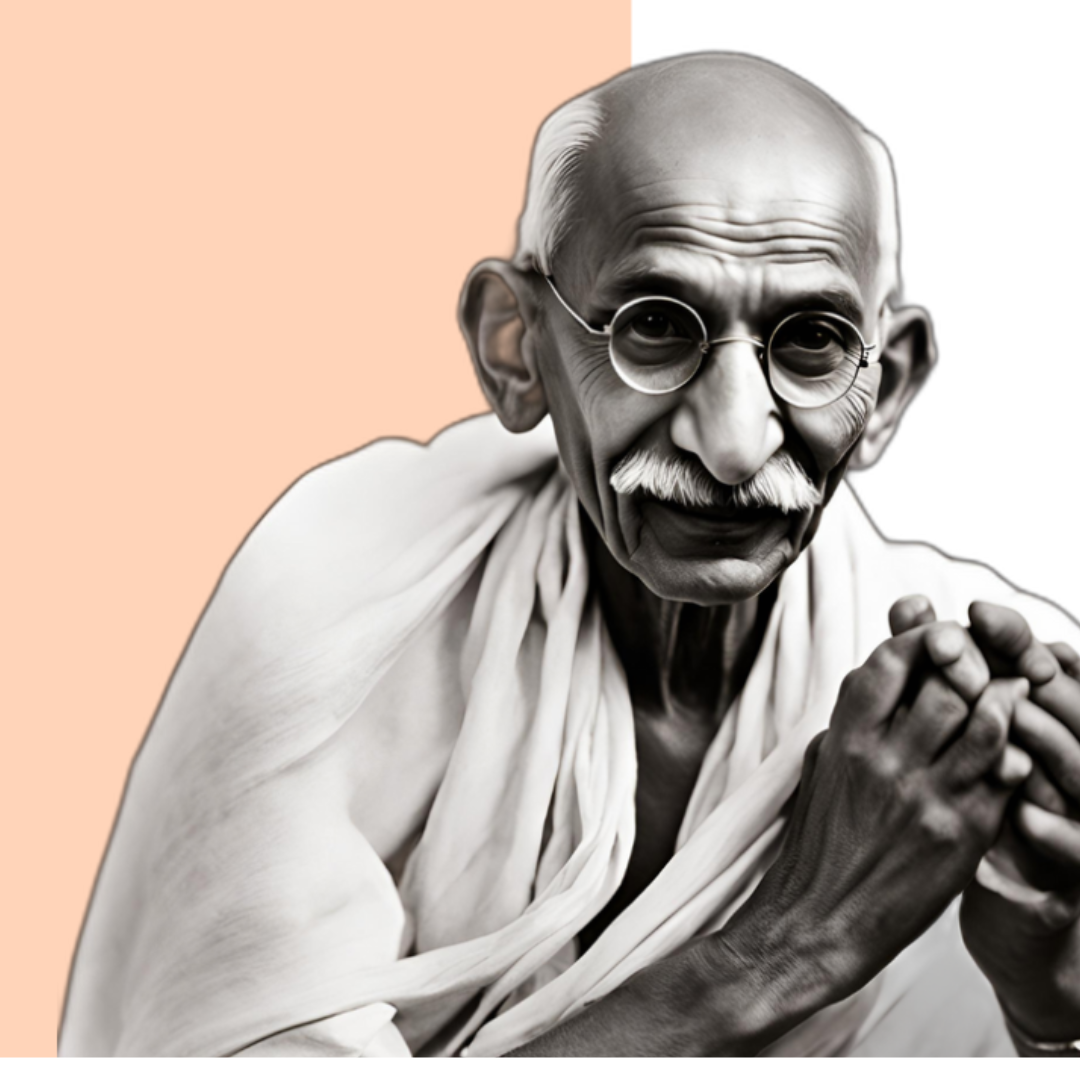

Mahatma Gandhi is one of the most well-known and respected figures in the history of the world. He is often called the “Father of the Nation” in India because of the huge role he played in the country’s struggle for independence from British rule. But Gandhi was more than just a political leader—he was also a thinker, a reformer, and a man deeply committed to truth, peace, and non-violence. Gandhi was born in a small town in Gujarat, and his journey from a regular boy to a world-famous symbol of peace and justice is truly inspiring and full of lessons. His unique method of fighting injustice without using violence, known as Satyagraha, has influenced many other leaders across the world, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela. In this article, we will explore the life of Mahatma Gandhi in detail—his early life, his time in South Africa, his leadership in India’s freedom movements, his beliefs and values, and the lasting impact he left behind. We will also look at some of the challenges he faced, the criticisms against him, and how he responded to them. Whether you’re learning about Gandhi for the first time or want to understand him more deeply, this article will give you a complete picture of who he was and why he still matters today.

Early Life and Education (1869–1893)

Mahatma Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in a small town called Porbandar, in the present-day Indian state of Gujarat. His full name was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. His father, Karamchand Gandhi, worked as a Dewan (chief minister) in a local princely state, and his mother, Putlibai, Gandhi’s mother, was very religious and taught young Mohandas to be honest, kind, and simple through her way of living. Gandhi grew up in a traditional Hindu family. As a child, he was shy and quiet. He wasn’t an outstanding student, but he was sincere, disciplined, and respectful. At the age of 13, he was married to Kasturba Gandhi, as was common at the time in Indian society. The early marriage brought many responsibilities, and later in life, Gandhi often reflected on how it affected his youth. After finishing school in India, Gandhi went to London in 1888 to study law. This was a big change for him. He had never left India before, and British culture was very different. In the beginning, he struggled with language, food, and social customs. But over time, he adapted and started reading religious and philosophical books. This was when he came across the teachings of Jesus Christ, Leo Tolstoy, and the Bhagavad Gita—all of which would later shape his thinking. Gandhi finished his law studies and came back to India in 1891, hoping to work as a lawyer. However, his early attempts as a lawyer were not very successful. Soon, an unexpected opportunity took him to South Africa, where the next important chapter of his life would begin.

Gandhi in South Africa (1893–1915)

In 1893, Mahatma Gandhi got an offer to work as a legal advisor in South Africa for an Indian businessman. He accepted the job and traveled there, not knowing that this trip would completely change his life and shape his future mission. Soon after arriving, Gandhi faced racism and discrimination in a direct and painful way. On one occasion, even though he had a valid first-class train ticket, he was thrown out of the compartment just because he was not white. This event happened in Pietermaritzburg, and it deeply shocked him. It made him realize that people of color, especially Indians in South Africa, were treated unfairly and had no real rights. Instead of returning home, Gandhi decided to stay and fight against injustice. But he didn’t believe in using violence. He started a new method of protest based on truth and non-violence, which he called Satyagraha. His idea was clear and strong: fight unfair treatment in a peaceful way, with bravery and patience. He lived in South Africa for 21 years, where he led many protests, started the Natal Indian Congress, and helped unite Indian people to fight for their rights. He also began living a simple life—giving up fancy clothes, practicing vegetarianism, and doing regular manual labor. He created two small communities, Phoenix Settlement and Tolstoy Farm, where people lived equally, regardless of religion or background. During this time, Gandhi also improved his public speaking and leadership skills. He earned the respect of both Indians and many local South Africans. When he left South Africa in 1915, he was no longer just a lawyer—he had become a leader and reformer, ready to fight for India’s freedom.

Entry into Indian Politics and Early Movements (1915–1920)

When Gandhi returned to India in 1915, he was already well-known because of his work in South Africa. People admired his courage and his peaceful way of fighting injustice. But instead of jumping straight into politics, Gandhi spent his first year traveling across India to understand the real problems of the people. He visited villages, talked to farmers, workers, and ordinary citizens. He wanted to see their struggles with his own eyes before trying to lead them. During these travels, Gandhi saw deep poverty, unfair taxes, and British cruelty, especially in rural areas. He believed that India could only become free by helping the people directly and making them part of the struggle. His first major involvement in Indian public life came in 1917 in Champaran, Bihar. British landlords were forcing poor farmers to grow indigo and sell it at unfair prices. Gandhi went there, listened to the farmers, and launched a peaceful protest. His efforts were successful, and the British had to accept the farmers’ demands. This was called the Champaran Satyagraha, and it made Gandhi a hero among the poor. Soon after, he led another movement in Kheda (1918), where farmers were suffering from famine but were still forced to pay taxes. Again, Gandhi used non-violent protest, and the government gave tax relief. Around the same time, he also helped workers in Ahmedabad during a strike, supporting them as they fought for better wages. Gandhi stood by their side with truth and courage. These early wins showed that Gandhi’s way of using peace and non-violence could truly make a difference. People from all parts of India—rich and poor, Hindu and Muslim—started to believe in him. He also became a major voice in the Indian National Congress, the main political party fighting for independence. By 1920, Gandhi was ready to take the fight against British rule to a national level. A much bigger movement was about to begin.

The Non-Cooperation Movement (1920–1922)

By 1920, Gandhi had become a strong national leader, and millions of Indians trusted him. People believed he could help free the country from British rule. Around this time, many Indians were angry with the British for two major reasons: the harsh Rowlatt Act, which allowed the government to arrest people without trial, and the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919, where British soldiers killed hundreds of innocent people gathered in Amritsar. Gandhi felt it was time for the whole country to peacefully stop working with the British. This idea became known as the Non-Cooperation Movement. The message was clear: if Indians stopped following British rules and stopped helping them, their power would grow weak and collapse. Gandhi asked the people of India to stop helping the British. He told them not to buy British clothes and to wear homemade clothes instead. He asked students to leave British schools and government workers to quit their jobs. He also told people to give up British titles and stop paying some taxes. These peaceful actions were meant to show that Indians no longer accepted British rule. This movement spread like wildfire across the country. People burned foreign clothes in public, students left English schools, and lawyers gave up their practice. Gandhi’s message reached the common people, especially villagers, who now felt they were part of the freedom struggle. But in 1922, something happened that made Gandhi stop the movement. In a small town called Chauri Chaura in Uttar Pradesh, a group of angry protestors set a police station on fire, killing several policemen. Gandhi was deeply upset because the movement had turned violent, even though he had always preached non-violence. He believed the people were not yet fully ready to follow his peaceful path. He quickly ended the movement and took full responsibility for it. Many leaders were shocked and disappointed, but Gandhi stood by his belief that how you fight is just as important as what you’re fighting for. Soon after, he was arrested and sent to prison for six years, but he was released after two years due to health problems. Even though the movement ended early, it had a huge impact. For the first time, millions of ordinary Indians had joined hands against British rule. It showed that people were ready to fight—not with weapons, but with unity and truth.

Civil Disobedience and the Salt March (1930–1934)

After the Non-Cooperation Movement, Gandhi stayed away from active politics for a few years. But by 1930, he felt the time had come for another major national protest. The British were still treating Indians unfairly, especially through heavy taxes and economic control. One of the most unjust British rules was the salt tax—even though salt was a basic need for everyone, Indians were not allowed to make it themselves and had to buy it from the British. Gandhi chose salt as a symbol of protest because it was simple, essential, and connected to every Indian, rich or poor. He believed that peacefully breaking the salt law would send a strong message to the British government. On March 12, 1930, Gandhi started the famous Salt March, also known as the Dandi March. He walked 240 miles from his home in Sabarmati to the coastal village of Dandi in Gujarat. He was 61 years old at the time. Thousands of people joined him during the walk to show their support. On April 6, Gandhi reached the seashore and made salt from seawater, breaking the British law in a peaceful and symbolic act. This moment inspired millions across India. People everywhere began making their own salt and protesting British laws without violence. This movement was called the Civil Disobedience Movement. The British responded harshly. Thousands of people, including Gandhi, were arrested and put in jail. But the movement continued. Women, students, and even villagers took part in large numbers. It was a time when the whole country was waking up—people were no longer afraid of the British. In 1931, Gandhi was released and went to London for the Second Round Table Conference to discuss India’s future. But the talks failed, and no proper agreement was made. Gandhi came back to India and started the movement again, but this time it was not as strong as before. By 1934, Gandhi decided to take a break from Congress politics and focus on helping villages, promoting khadi (homemade cloth), and bringing people together. Even though the Civil Disobedience Movement didn’t bring freedom right away, it strengthened the national spirit and proved that peaceful protest could challenge even a powerful empire.

Quit India Movement and Final Struggle (1942–1947)

By the early 1940s, the world was in the middle of World War II, and India was still under British rule. Without asking Indian leaders, the British dragged India into the war. This caused anger and frustration all over the country. Gandhi believed the time had come for the final push for freedom. He was now sure that the British must leave India immediately. In 1942, Gandhi started the Quit India Movement, with the powerful slogan: “Do or Die.” He told the British to leave India and asked Indians to fight for their freedom with complete unity and non-violence. It was one of the strongest and boldest calls for independence. The British were shocked by the strength of the movement. In response, they acted fast. Within hours, Gandhi and almost all the top Congress leaders were arrested and put in jail without a trial. Gandhi was kept in Aga Khan Palace in Pune. While in prison, he suffered great personal loss. His wife, Kasturba Gandhi, died there in 1944, and Gandhi also became very sick. Even without its leaders, the movement spread across the country. People held protests, went on strike, and broke unfair laws. The British responded with violence, arrests, and even shootings. But by now, the spirit of the Indian people was too strong to be broken. During this time, Gandhi also worked hard to reduce rising tensions between Hindus and Muslims. He was completely against the idea of dividing India. But many Muslim leaders, especially the Muslim League led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, were demanding a separate country called Pakistan. By the end of World War II in 1945, the British had become weak, both politically and economically. They realized they could no longer rule India. After long talks and increasing pressure, the British finally agreed to leave. But independence came with great pain. In 1947, British India was divided into two countries—India and Pakistan. This Partition led to terrible violence, especially between Hindus and Muslims. Gandhi was heartbroken. Even though the country was free, the happiness was darkened by bloodshed, loss, and hatred. Still, Gandhi didn’t give up. He spent the last months of his life traveling from village to village, trying to bring peace, stop the violence, and heal the wounds of Partition.

Beliefs, Philosophy, and Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi was not just a political leader—he was also a spiritual teacher, a reformer, and a man who lived by strong values. His ideas were simple but very powerful. They came from his own life experiences, deep thinking, and reading. At the center of his beliefs were truth, non-violence, and self-control. Gandhi strongly believed in Satya (truth). To him, truth wasn’t just about telling the truth—it meant living truthfully, with honesty in every part of life. He believed that real freedom and justice could not exist without truth. Another important belief of Gandhi was Ahimsa, which means non-violence. He believed that violence only creates more hate. He taught that people can fight against injustice without using force. He believed that love, patience, and understanding were better and stronger than guns or violence. This idea inspired not only Indians but also people in other countries, like Martin Luther King Jr. in the United States and Nelson Mandela in South Africa. Gandhi also believed in Swaraj, which means self-rule. But for him, it was more than just political freedom. It also meant self-control, self-reliance, and living with strong moral values. He wanted every Indian to live simply, wear clothes made by themselves (khadi), eat local food, and support village life. He believed India’s real strength was in its villages, not in big cities or Western-style development. Gandhi worked hard to end untouchability and wanted a society where all people were treated equally, no matter their caste or religion. He called the Dalits “Harijan,” which means “people of God,” and tried to help them live with respect and gain their rights. Even though he followed Hindu traditions, Gandhi deeply respected all religions. He often read from the Bhagavad Gita, the Bible, and the Quran. He believed that all faiths teach love and kindness, and always encouraged unity between Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, and others. His lifestyle matched his beliefs. He wore simple clothes, lived in small huts, ate plain food, and practiced regular fasting—not just for health, but as a way to cleanse the soul and stay humble. Gandhi’s legacy lives on not just in India, but all over the world. His ideas of peaceful protest, equal rights, and human dignity continue to inspire people who fight for justice and peace.

The Assassination of Gandhi

After India gained independence in 1947, Gandhi should have been celebrating. But instead, he spent his final months trying to heal a broken nation. The country had been divided into India and Pakistan, and this Partition caused terrible violence. People were killed, homes were burned, and families were torn apart. Gandhi was heartbroken. He went from village to village, urging people to stop fighting and live in peace. He also fasted several times, putting his life at risk to stop the bloodshed. His goal was to unite Hindus and Muslims and remind them that they were brothers. But not everyone agreed with him. Some people felt he was being too soft on Muslims or giving too much to Pakistan. Sadly, this hatred led to a terrible tragedy. On the evening of January 30, 1948, while Gandhi was walking to his daily prayer meeting in Delhi, he was shot and killed by a Hindu extremist named Nathuram Godse. The entire country—and the world—was shocked and deeply saddened. Gandhi didn’t hold any official position. He had no army, no wealth, and no weapons. Yet, through truth, non-violence, and love, he helped free one of the largest nations in the world. His life proved that one person, with strong beliefs and a kind heart can change history. Even today, Gandhi is remembered as the “Father of the Nation” in India. His teachings are still studied in schools and followed by leaders across the world. Statues of him stand in many countries, and his birthday, October 2nd, is celebrated as Gandhi Jayanti and also recognized as the International Day of Non-Violence by the United Nations.

Conclusion

Mahatma Gandhi was a truly remarkable leader who changed the course of history through peace, not violence. He believed in truth, non-violence, and self-discipline, and he practiced these values in every part of his life. Gandhi led India’s freedom struggle in a way that inspired the world, proving that real strength comes from courage, patience, and love—not from weapons or hate. Even after his death, his teachings continue to guide people everywhere who are fighting for justice, equality, and peace. Gandhi’s life reminds us that one person, with strong beliefs and a kind heart, can make a big difference in the world.

Your ability to connect with the reader on both an intellectual and emotional level is truly rare.

Pingback: History of India